There seem to be a widespread opinion that hygiene by bathing had its highlights during roman and medieval period, only to decline drastically during the 16th century. The Dutch philosopher Erasmus in 1526 noted the fall of common hygiene: “Twenty-five years ago, nothing was more fashionable in Brabant than the public baths. Today there are none, the new plague has taught us to avoid them”.

Yet bathing, both alone and in group, seems to persist during the 16th century. At least depictions of bathing people remain popular during the period. Browsing through these early modern nudies I spot a remarkable hat that seems only to show up in bathing situations. It is round, slightly squarish and sometimes with a little tuft on the top:

The text of the Nuremberg bathmaid above translates:

The speech of the bathmaid: I the bathmaid stand alone, with naked arms and white legs. I tend to the bathing men, also the young boys. With my water I am skilled, young and old, the little child, I wash, and I scrub them, so they go home clean.

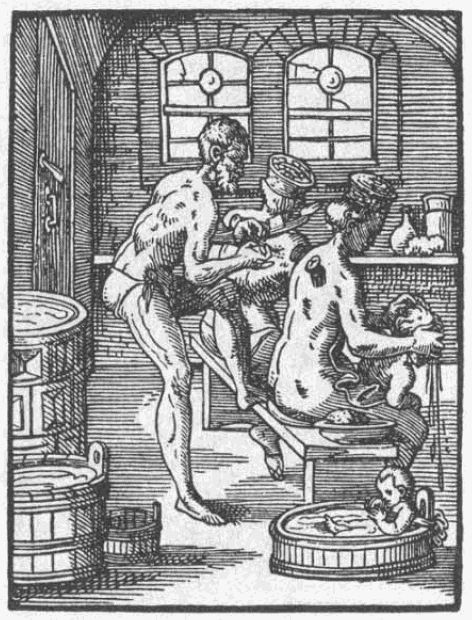

A somewhat basic everyday cleanliness seems to be expected of the 16th century person: Washing the hands before eating is emphasized in manners manuals of the 15th and 16th century, as well as washing hands and face in the morning and rinse the mouth with cold water. Babies were bathed in tubs, and rather ingeniously binded in the tub to ensure its safety and let the parents have some cupping therapy and wash the older sibling, in the already mentioned bathing hat:

Bathers from Das Ständebuch (The Book of Trades), 1568

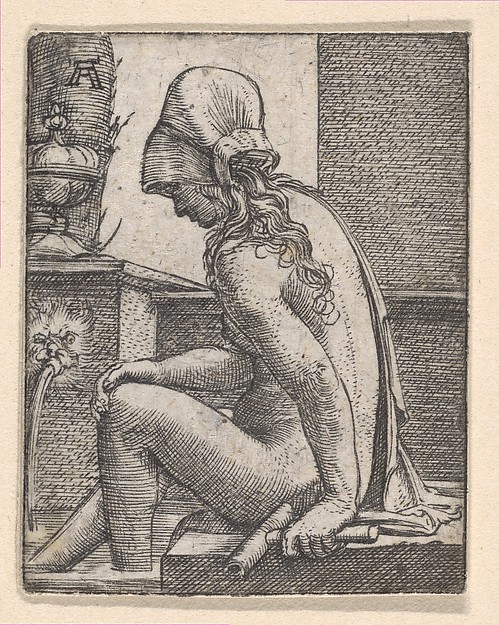

The theory that people ceased bathing altogether during the 16th century isn’t at all reflected in pictures from the period, as we can see. In fact, even though mixed bathing was discouraged by the Church, records exist that “baths were used as social affairs, with banquets and wedding feasts being joined with the baths”. But Durer’s 1497 woodcut of men at a public bathhouse, contrasted with ‘Women’s Bath’ of the same year shows sex-segregated bathing as well as the little rounded bath hat we’ve already peeked at:

“The Men’s Bath” Albrecht Dürer (1497 Nuremberg)

As we can see in the pictures above and below the habit of head gears follow the early modern people even into the bathroom – we have trendy hairnets on men, braided hairdo’s or headscarfs on the women or bathing hats on both genders. If not naked, men seemed to wear the male tanga we’ve already talked about, and women in a simple linnen underdress.

The gentlemen prefering a slightly more discrete but fast hair wash could also get that done at the barbers, as shown in this late 16th century woodcut (please also note the casual way the barber keeps his comb behind the ear):

Washing, alone or in group, certainly persisted. We see combinations of bathing or washing in bathhouses (in- aswell as outdoors) or bathtubs. In 1511 Lucas Rem, a famous 16th century merchant and diary writer, according to his diary allegedly bathed 127 times (!) from the 20th of may to the 9th of june. Sources does seem to indicate though, that bathing was for the spring and summer, while washing, atleast in public places or outdoors, probably declined somewhat during the winter months…

“A fool with two bathing women”, Hans Sebald Beham (1541)

Also, scented soaps for face and hand-washing (made by the ‘rebatching’ process where cut-up soap is mixed with scenting agents) starts to appear in 16th and early 17th century housewifery texts. The 16th century Spanish Manual de Mugeres suggests some scented soap recipes and Francis Bacon (1521-1626) recommends a saucy bath in oil and herbs for the best result:

First, before bathing, rub and anoint the Body with Oyle, and Salves, that the Bath’s moistening heate and virtue may penetrate into the Body, and not the liquor’s watery part: then sit 2 houres in the Bath; after Bathing wrap the Body in a seare-cloth made of Masticke, Myrrh, Pomander and Saffron, for staying the perspiration or breathing of the pores, until the softening of the Body, having layne thus in seare-cloth 24 hours, bee growne solid and hard. Lastly, with an oynment of Oyle, Salt and Saffron, the seare-cloth being taken off, anoint the Body.

Woodcut from “Buch zu Distillieren” (1500)

The love of bringing nice scents into the cleaning ritual we also witness through Adamus Olearius in his Persian Travel Tales of the early 1600s: “The Germans who dwell in Muscovy and Livonia are very nice in their Stoves; they strew Pine Leaves powder’d, and all sorts of Herbs and Flowers upon the Floor; which, together with the Lye make a very agreeable Scent.”

There is a scented lye-based soap recipe in The treasurie of commodious conceits, & hidden secrets by John Partridge (1573) if anyone wishes to try the 16th century BO for a spin:

To Make Muske Soape Take stronge lye made of chalk, and six pounde of stone chalk: iiii, pounde of Deere Suet, and put them in the lye; in an earthen potte, and mingle it well, and kepe it the space of forty daies, and mingle and [styre?] it, iii, or, iiii times a daye, tyll it be consumed, and that, that remayneth, vii, or, viii, dayes after, then you muste put a quarter of an ounce of Muske, and when you have done so, you must [styre?] it, and it wyll smell of Musk.

Suggested further reading, for the curious:

→ Did people in the middleages take baths?

“… seized bathing”? Pretty sure you meant ‘ceased bathing’.

LikeLike

And it’s linen not linnen.

Aswell is not a word but “as well” is a phrase.

May and June are nouns and, therefore, require capital letters.

“Sources do … ” not “Sources does …”

‘Atleast’ is not a word. It is a two word phrase.

LikeLike

Thank you for you input, friend of order! I’ll update the entry when I have time.

But I hope that my readers out of the kindness of their heart can overlook a few spellings errors, as I’m not born English speaking and our way of both spelling some words and building sentences differ from the English language, and might lead to some strange and exotic errors. The spell checker is generally my friend.

Have a great weekend!

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading your interesting and informative article, and your use of illustrations to support your research was very helpful. Your use of English is clear and concise. It is generous of you to share your information in another language! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your lovely comment! It really inspire me write here more often – 2020 will be the year!

Thanks again! ❤

LikeLike

Reblogged this on La Bella Donna.

LikeLike

Very interesting article! I had not thought 16th century people bathed so often. But it makes perfect sense, otherwise how could they stand to be near each other!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello and thank you so much for your comment! Im happy you liked this well washed entry and yes, I think we have to revise the way we think about cleanliness back in the days. It is not a modern invention to like a good bath! 🙂

LikeLike

I’ve always been skeptical of the nigh-universally accepted belief that Europeans of the medieval and renaissance eras were all filthy as pigs and never bathed. I’ve always wondered if the myth didn’t grow so universally accepted because there _were_ some Christian ascetics who eschewed bathing as part of their mortification of the flesh, and because Louis XIV was apparently terrified of bathing and according to some authors, only did so three times in his life (which is almost certainly an exaggeration — and I think people are assuming the French and other European nobility did as well, because royalty set the fashion.

It is true that the Russian ambassador to the court of Louis XIV of France noted that the king “stank like a wild animal.” What I think they are missing is that the ambassador took care to observe specifically that the _king_ stank like a wild animal. If everyone had, he probably would have extended that observation to the rest of them, but he doesn’t, he singles Louis out.

LikeLike

Hello Darren and thank you so much for your comment!

I highly agree with your skepticism and think fully that the decline of personal hygiene probably began around 1700s as a trend that might have started with the sun king. But that doesn’t mean, as you so wrote, that everyone was constantly insanely dirty and afraid of water. You have a really good point with Louis XIV – why make a fuss over the kings horrid B.O if everyone had horrid B.O? There was the same observations made about Henry VIII – that he stank so bad that you could feel his smell from rooms away. But this wasn’t due to bad personal hygiene, but bevause he had a very big infected sore on his leg that never healed. And it the same here, why was Henrys terrible stink pointed out, if “everyone” was smelly and unclean during the times?

Im thinking that maybe also the fact that big cities DID stink in historical times, have made modern historians assuming that people there for also stank? Just a thought…

Thanks again for your awesome comment!

LikeLike